Parvovirus In CatsUpdated 6 months ago

Feline parvovirus (FPV), also called Feline panleukopenia virus (FPV), is highly contagious and infective immediately upon passing in a cat’s stool or respiratory secretions. Signs can range from mild digestive upset to severe diarrhea and death.

My Cat Tested Positive For Parvovirus

MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test with PCR Upgrade includes PCR assay tests for disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and protozoa found in cat intestines. One of those viruses is Feline parvovirus. A positive test means parvoviral DNA was detected in the stool. Most veterinarians then assume the cat is infected with parvo and shedding the viral particles (virions) in the stool. This viral shedding can represent an infection risk for other cats (and maybe dogs).

Important: If your cat or kitten has symptoms suspicious of parvo infection or has a parvo positive test result and either isn’t vaccinated for parvo or isn’t current (up to date) with parvo vaccination, then please consult with a veterinarian immediately! Parvo infections can progress from mild signs to life threatening illness in 12-24 hours.[2] Early treatment can sometimes be the difference between life and death, especially in young kittens (3 to 6 months) that are unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated.

A positive finding is not always associated with symptoms of illness and may not require treatment. Most properly vaccinated cats infected with parvo will quickly suppress the parasite and never get sick or only have mild symptoms, but can still shed the virus.[2,9] It’s important to confirm with your veterinarian that your cat or kitten is current (up-to-date) with parvo vaccinations.

The PCR test can detect modified-live parvo vaccine virus in the stool for up to 3-4 weeks (usually only 1-2 weeks) after administration of the vaccine.[2,9] The cat is truly shedding parvovirus but it’s the vaccine virus, which is a good thing and not a health risk to other cats or dogs.

A test result is not the same as a veterinarian’s diagnosis, so it’s always best to consult with a veterinarian about your cat’s test results to determine the safest and most effective treatment and prevention plan, and when to do follow-up stool tests. Some veterinarians may recommend rechecking a cat’s stool sample within 2-4 weeks after detection of parvo to confirm that the shedding has stopped. Parvo shedding can be a risk to other cats (and maybe dogs) so these cats should be isolated if possible until the shedding has stopped. Some cats can continue to test positive for parvo for an unknown period after treatment. This is most likely because the cat remains in an environment where re-infection keeps occurring.

MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test includes a reference lab stool O&P (fecal ova and parasites) which screens for roundworms, hookworms, tapeworms, whipworms, and some types of coccidia. Viruses (like parvovirus) and bacteria are not visible on this type of test which is why PCR testing (MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test with PCR Upgrade) is needed.

The MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test with PCR Upgrade screens for all five cat and dog parvo strain types (FPV, CPV-2, CPV-2a, 2b, 2c). PCR can be used to distinguish between the parvovirus strain types, but this is rarely necessary. The approach to treatment and prevention is assumed to be the same regardless of strain.[7,8] For this reason a MySimplePetLab parvo positive result does not distinguish between parvo strain types.

My Cat Tested Negative For Parvovirus

MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test with PCR Upgrade includes PCR assay tests for disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and protozoa found in cat intestines. One of those viruses is Feline parvovirus. A negative test means parvoviral DNA was not detected in the stool from any of the five cat or dog strain types (FPV, CPV-2, CPV-2a, 2b, 2c). That’s great news. No one wants their cat or kitten shedding these viral particles (virions) and maybe putting other cats (or maybe dogs) at risk of infection.

Important: If your cat or kitten has symptoms suspicious of parvo infection and isn’t vaccinated for parvo or isn’t current (up to date) with parvo vaccination, then please consult with a veterinarian right away. Parvo infections can progress from mild signs to life threatening illness in 12-24 hours.[2] Early treatment can sometimes be the difference between life and death, especially in young cats (3 to 6 months) that are unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated.

Most clinically ill cats shed large amounts of viral particles in their stool but maybe only for 1-2 days, so a “false (incorrect) negative” is possible even if the cat is showing symptoms. Shedding may not have started if early in infection or have stopped if late in the course of infection. These are situations where a PCR test could come back negative (falsely), but the cat or kitten was truly infected with parvo. Please consult with a veterinarian right away if your cat is negative on parvovirus by PCR but still with parvo-like symptoms such as vomiting and abnormal stools.

Depending on their lifestyle, cats can remain at risk of parvo exposure so a negative test result today doesn’t mean it couldn’t be positive later.

Learn More About Parvovirus

What Is Parvovirus?

Feline parvovirus (FPV) is a very serious, even fatal viral pathogen of kittens and cats. This is why veterinarians administer a series of parvo vaccinations to kittens with vaccine boosters to protect adult cats over their lifetimes.[6] If there is just one learning about FPV, it’s to vaccinate cats for parvo early and often. Parvovirus is essentially everywhere and can cause awful symptoms in unvaccinated or not fully vaccinated (up to date) cats. Fortunately, modern parvo vaccines are extraordinarily safe and effective, making this an easily preventable disease in most kittens and cats.[6]

Most cats that get exposed to Feline parvovirus stay healthy and don’t show symptoms.[7,8] If they do get sick, illness can be mild or progress quickly and be severe. The pet’s age, stress level, co-infections and immune strength can all influence the response to infection.[7,8] Young kittens (3 to 6 months of age) are especially vulnerable.[2]

Parvo can be dangerous to cats and kittens because it attacks the lymph nodes and bone marrow (weakening the immune system) while at the same time damaging the small intestinal lining (hampering the gut barrier). This injury to the intestine allows gut bacteria to escape from the digestive tract and into the bloodstream (bacteremia). This combination of viral and bacterial waves of infection can damage many body systems (including heart, skin, and brain). It’s damage to the small intestine that leads to the classic symptom in cats: vomiting (often with bile) and diarrhea.[1,7]

History of Parvo: Feline parvovirus (FPV) is also called Feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). It is often mistakenly referred to as “distemper” which it isn’t. The confusion comes in comparing it to dog viral infections. Canine distemper is an RNA morbillivirus while Canine parvovirus is a DNA parvovirus. Feline panleukopenia virus is also a DNA parvovirus, which is why referring to it as “parvo” in cats is correct while “distemper” is not.

The origin stories of Canine parvovirus (CPV) surprisingly starts with cats. Feline parvovirus (FPV) infection of domestic and wild cats was first identified in the 1920’s. In the mid-1970’s in Europe it mutated to create a new type of parvovirus that jumped to dogs. The dog type (called “CPV-2”) was also highly contagious and often fatal, and quickly spread around the world as an epidemic, killing many thousands of dogs.[3,8]CPV-2 was eventually brought under control with the development of the Canine parvovirus vaccine.

The CPV-2 strain type lost the ability to re-infect cats and became a dog-only virus. Cats still got infected with their original FPV while dogs got infected with the new CPV-2.[3] Then about 1980 CPV-2 genetically mutated to form the CPV-2a type, and about 1984 CPV-2a mutated to form the CPV-2b type, and in 2000 the CPV-2c strain appeared.[3] The original FPV is still not infective to dogs, however all of these new strain types (CPV-2a, 2b, 2c) are infective to dogs and regained the ability to infect cats.[3] For dogs in the U.S., CPV-2b is the most common strain type causing illness.[2] The association between severity of clinical signs and the parvo strain type is uncertain in cats.[2] Feline parvo vaccinations appear to help protect cats and kittens against these newer Canine parvo strain types.[2]

How Common Is Parvovirus?

Feline parvovirus (FPV) is highly contagious and a relatively common cause of intestinal distress, especially in young animals.[2]It causes infections in domestic cats and wild felids.[2] FPV can be found all over the world and is able to infect all breeds and ages of cats.

Most cats that get exposed to Feline parvovirus stay healthy and don’t show any symptoms.[2,8] If they do get sick, clinical signs are usually most severe in young, rapidly growing kittens that haven’t started or finished their parvo vaccination series. Infected cats and kittens are at higher risk if also infected with other pathogens such as Feline leukemia virus, Feline coronavirus, or Salmonella spp.[2,7]

Healthy-appearing cats can shed parvo in their stool but also through respiratory secretions (coughing, sneezing, eyes/nose drainage). Assume that parvo is wherever cats are housed or play together (catteries, multi-cat households, shelters). It is one of the most resistant viruses to infect cats, even to common detergents and disinfectants.[2,7] Parvo can survive in the environment for long periods of time (even through the winter).[2,7] It can remain infective indoors at room temperature for 1-2 months and outdoors, if protected from sunlight and drying, many months or maybe years.[2,7] Parvo prefers dark, moist locations to survive outside of the cat.[5] This virus can even survive on cat’s hair coat for extended periods.[7]

Since the development and advancement of parvo vaccines, this virus is much less of a threat to the modern cat.[5] Thanks to widespread vaccination, clinical disease from parvo has been dramatically reduced compared to decades ago. Keep in mind that vaccination doesn’t prevent the cat from getting exposed to the virus in the environment, doesn’t prevent the cat from getting infected with parvo, nor prevent the cat from shedding the virus (in their stool or from their nose or mouth). Instead, vaccination prepares the cat’s immune system (antibodies) to aggressively defend the body if/when the real virus attacks. A properly vaccinated cat is very likely to fend off the viral attack and get only mild symptoms or not get sick at all. Simply put, the vaccine prevents cats and kittens from getting severely ill or dying from parvovirus.

What Does Parvovirus Look Like?

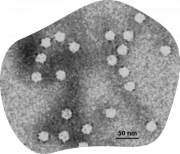

Viruses are a lot smaller than bacteria and not visible with the magnification of a regular, optical microscope at a veterinary office or laboratory. This means that special types of testing are required to detect their presence in samples.

Parvovirus belongs to the Parvoviridae family. The name comes from the Latin parvum, meaning small or tiny, as these are some of the smallest known viruses (~25nm).[7] Parvo is a single-stranded DNA virus with a protective (non-enveloped) protein coat called a capsid. This impenetrable capsid shell protects the viral DNA. Unlike viruses enveloped (wrapped) in a lipid (fat) layer (e.g., coronavirus), non-enveloped viruses like parvovirus are very durable in the environment and resistant to many detergents and disinfectants.[2]

Viruses are not visible on a fecal O&P (ova (egg) and parasite) stool test (included in MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test). The O&P looks for worms and some types of coccidia, not bacteria and not viruses. Most of the time, a special Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test is used to detect the presence of parvovirus in cat stool (MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test with PCR Upgrade).

What Symptoms Are Caused By Parvovirus?

Many cats that get exposed to Feline parvovirus stay healthy and don’t show any symptoms.[2,7] If they do get sick, symptoms can progress quickly and be severe.

The pet’s age, stress level, co-infections, and immune strength can all influence the response to infection.[7,8] Young kittens (3 to 6 months of age) are especially vulnerable.[2] Exposure to parvo during times of stress (from weaning, overcrowding, or poor nutrition) or other pathogen infections (Salmonella spp., Leukemia virus, coronavirus) can increase the severity of illness.[2]

Sometimes cats exposed to parvo stay healthy because the exposure dose (number of parvo viral particles) was low or their immune system was able to suppress it.[8] More likely it is because the cat or kitten was previously and properly vaccinated against parvo.

Parvo is dangerous to cats and kittens because it attacks the lymph nodes and bone marrow (weakening the immune system) while at the same time damaging the small intestinal lining (hampering the gut barrier). This injury to the intestine allows gut bacteria to escape from the digestive tract and into the bloodstream (bacteremia). The debilitated immune system must then defend against both the multi-organ viral attack and this whole-body bacterial invasion.[2]

This combination of viral and bacterial waves of infection can damage many body systems (including heart, skin, and brain). It’s damage to the small intestine that leads to the classic symptom of vomiting (often with bile) and diarrhea.[8] Symptoms may start with lethargy, depression, and decreased appetite, but progress to high fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, and sometime diarrhea.[1,7] If untreated this can quickly lead to dehydration, hypothermia (low body temperature), sepsis (bacteremia), toxic shock, and death.[2,7]

Many veterinarians have treated cats with parvo and seen firsthand how awful this disease can be, which is why they so strongly recommend parvo vaccinations to kittens and cats throughout their lives.

How Do Cats Get Parvovirus?

Cats get exposed to parvovirus from close contact with a cat actively shedding the viral particles (virions), or by being in an indoor (household, cattery, shelter) or outdoor environment contaminated by an infected cat maybe days, weeks, or months prior.[2] Unlike many other parasites (e.g., most worms, coccidia, Salmonella), swallowing parvo isn’t necessary to get sick. The infection starts in the lymph nodes of the mouth and throat, and spreads throughout the body into bone marrow and the lining of the small intestines. Parvo gets into the cat’s mouth from licking the floor or toys, bedding, dishes, by eating soil, grass, or plants, or drinking water that had been contaminated with the virions.

Humans can contribute to spreading parvo on their shoes, equipment, or on their hands after handling infected dogs. Even insects and rodents can be responsible for inadvertently transporting virions around animal housing facilities.[7]

Infected cats can shed parvo particles (virions) in their stool, urine, and respiratory secretions (coughing, sneezing, nose/mouth licking/grooming), infecting other cats and contaminating the environment with long-lasting virions. The shedding often lasts just 1-2 days during the illness, but can persist another 6 weeks after recovery.[2] Properly vaccinated kittens and cats exposed to parvo should be able to suppress the infection and not get sick. However, they can still be shedding the virions while appearing perfectly healthy. These virions shed from vaccinated cats can still infect other cats.

Kittens are more likely to get sick than older cats.[2] Cats that are immune-suppressed, fighting off other infections (intestinal pathogens), and/or in stressful conditions (like being transported/relocated or housed in groups) are more likely to get sick with parvovirus (vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration).[2]

Assume that parvo is wherever cats are housed or play together (catteries, multi-cat households, shelters). It is one of the most resistant viruses to infect cats, even to common detergents and disinfectants.[2,7]

What Is The Parvovirus Lifecycle?

Outside of the animal (host) cells, parvovirus takes the form of a particle called a virion. This is simply a single strand of DNA surrounded by a (non-enveloped) protein coat called a capsid. This impenetrable capsid shell protects the viral DNA when shed into the environment or while being transmitted directly to another cat.

Cats with parvo can shed these virions in their stool, urine, and respiratory secretions (coughing, sneezing, eyes/nose drainage), infecting other cats and contaminating the environment with long-lasting viral particles. The shedding often lasts just 1-2 days during the illness, but can persist another 6 weeks after recovery.[2] Properly vaccinated kittens and cats exposed to parvo should be able to suppress the infection and not get sick. However, they can still be shedding the virions while appearing perfectly healthy. These virions shed from vaccinated cats can still infect other cats.

Other cats get exposed from close contact with a cat actively shedding the virions, or by being in an indoor (household, cattery, shelter) or outdoor environment contaminated by an infected cat maybe days, weeks, or months prior.[2] Unlike many other parasites (e.g., most worms, coccidia, Salmonella), swallowing parvo isn’t necessary to get sick. The infection starts in the lymph nodes of the mouth and throat, and spreads throughout the body from there into bone marrow and the lining of the small intestines. Parvo gets into the cat’s mouth from licking the floor or toys, by eating soil, grass, or plants, or drinking water that had been contaminated with the virions.

The virion is the inert state (without metabolism or replication) of the virus, and only activates upon contact with an animal cell. Once parvovirus enters the new host animal, the parvo capsid shell of the virion “hooks” to a cat cell and injects the viral DNA into that cell. The animal (host) cell is then essentially hijacked and forced to produce thousands of identical copies of the original virus, which get released as virions to infect thousands of other cells in that animal. This process destroys the host cells, leading to clinical symptoms.

Since parvo first attacks the rapidly dividing cells of the immune system (lymph nodes and bone marrow) and intestinal lining, it can simultaneously weaken immune defenses (lowering the white blood cell counts) and attack the digestive tract.[2] This initial viral wave of infection can punch microscopic openings in the gut lining, releasing gut bacteria into the animal’s bloodstream without the protection of a strong immune defense.

This combination of viral and bacterial waves of infection can damage many body systems (including heart, skin, and brain). It’s damage to the small intestine that leads to the classic symptom of vomiting, sometimes with diarrhea.[7] Symptoms may start with lethargy, depression, and decreased appetite, but progress to high fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea (often with bile).[1,7] If untreated this can quickly lead to dehydration, hypothermia (low body temperature), sepsis (bacteremia), toxic shock, and death.[2,7]

Can People Or Other Pets Get Parvovirus?

Humans can get parvovirus infections but not from dogs or cats.[4]

People parvo is called “B19” and only infects humans, causing the syndrome “Fifth Disease”. This is mostly a childhood disease with mild rash symptoms.[4] It was “fifth” on the list of historical viral childhood infections, with measles, rubella, chicken pox, and roseola being the other four. B19 is spread between people through respiratory secretions (coughing, sneezing).[4] Cats and dogs are not at risk of getting parvo B19 from people.

Feline parvovirus (FPV) can cause illness in both domestic and wild cats but not dogs. In the mid-1970’s this virus mutated to create a strain (called CPV-2) that infected dogs. Canine Parvovirus (CPV-2) causes infections in domestic dogs and wild canines including coyotes and wolves, as well as other animals like foxes, raccoons, and skunks.[2] This original dog strain (CPV-2) lost the ability to cause illness in cats but newly evolved (and much more common) strains (CPV-2a, 2b, 2c) can cause disease in both dogs and cats.[3] The original FPV is still a cat-only virus, so a cat shedding FPV is not a risk to dogs. However, dogs shedding parvo (CPV-2a, 2b, 2c) can be a risk or transmission to cats.[3] Properly vaccinating cats for Feline parvovirus (panleukopenia) will protect cats against FPV and these canine strains.[5] Properly vaccinating dogs for Canine parvo will protect against all CPV strains.

How Is Parvovirus Prevented And Treated?

Prevention is boiled down to one word: vaccinate. Feline parvovirus is a necessary (core) vaccine for every kitten and cat, regardless of breed or lifestyle.[6]

Assume that parvo is wherever cats are housed or play together (catteries, multi-cat households, shelters). Even healthy-appearing cats can shed parvo is their stool or urine, but also through respiratory secretions (coughing, sneezing, nose/mouth licking/grooming). It is one of the most resistant viruses to infect cats.[2,7] Only take your kitten or cat to a cattery, grooming, or boarding facility where all cats are required to be current on immunizations.

Unlike viruses enveloped (wrapped) in a lipid (fat) layer (e.g., coronavirus), non-enveloped viruses like parvovirus are very durable in the environment. This makes these non-lipid (“naked”) viruses much more difficult to inactivate using common detergents and disinfectants or by subjecting them to temperature (sunlight) and pH extremes.[2] Parvo can survive in the environment for long periods of time (even through the winter).[2,7] It can remain infective indoors at room temperature for 1-2 months and outdoors, if protected from sunlight and drying, many months or maybe years.[2,7] Parvo prefers dark, moist locations to survive outside of the cat.[5] This virus can even survive on cat’s hair coat for extended periods.[7]

Preventing parvovirus is first about properly vaccinating but also requires a focus on hygiene. Parvo particles (virions) are highly contagious and infective immediately upon passing in a cat’s stool, so quickly remove stool and thoroughly clean indoor areas where cat stool has been present.[1] Steam and pressure washing may help to dislodge stool particles from kennel and cage surfaces. Painting and sealing kennel floors will help prevent stool from adhering to these surfaces while cleaning.[5] Respiratory secretions are also a common way for infected cats to spread virions, so avoid overcrowding or direct exposure to cats at high risk of shedding the virus. Also don’t be a “fomite”. In other words, human handlers can spread parvo with grooming equipment, cleaning tools, or just on shoes and hands between cats if not careful.

Though parvovirus is hardy, it can be destroyed with specific disinfectants.[5] Diluted household bleach (sodium hypochlorite) can be effective, at 1:30 concentration with water, as long as there is a minimum 10 minutes of exposure time.[5,7] This can be used to scrub kennels and cages, utensils, toys, and food dishes. Other effective bleach-like products include Wysiwash® and Bruclean®.[5] The disadvantage to these products is that surfaces need to be very clean for them to work, so they are better for stainless steel or sealed floors than for wood, carpet, unsealed concrete, or scratched plastic where stool or respiratory material can get embedded and deactivate these disinfectants.[5] On these more porous materials, Trifectant ® and Accel/Rescue® have better activity.[5] Bleach can be added when washing bedding materials and fabric toys. Steam cleaning can be used to instantly disinfect surfaces that don’t tolerate bleach.[5,7]

Treatment decisions for sick cats are based on the severity of symptoms. Antidiarrheal medications are not usually recommended so that the digestive tract can be cleared of the stool and gut microbes. Antibiotic therapy is for bacteria and has no effect on viruses. Antibiotics are not recommended for cats who have no symptoms or mild signs that respond to supportive therapy like hydration, rest, and digestive support. Outpatient treatment for mild cases might include antiemetics (e.g., maropitant) to stop the vomiting, hydration, and careful nutritional support. Cats with symptoms from parvo may need hospitalization and even intensive care, including intravenous (IV) fluids, electrolytes, nutrition, antibiotics (if sepsis suspected), antiemetics, etc.[2]

Where Are Parvovirus Medications Purchased?

MySimplePetLab does not dispense or prescribe medications, and there are no FDA-approved antiviral medications in the U.S. for Feline parvovirus treatment. A positive finding of parvo does not always signal a need for treatment. Properly vaccinated cats should be able to suppress the infection and remain healthy or get only mild symptoms. An unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated cat or kitten is at much higher risk.

Important: Cats or kittens with symptoms suspicious of parvo infection should consult with a veterinarian right away. Parvo infections can progress from mild signs to life threating illness in 12-24 hours.[2] Early treatment can sometimes be the difference between life and death, especially in young cats (3 to 6 months) that are unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated.

Therapy decisions for sick cats are based on the severity of symptoms. Antidiarrheal medications are not usually recommended so that the digestive tract can be cleared of the stool and gut microbes. Antibiotic therapy is for bacteria and has no effect on viruses. Antibiotics are not recommended for cats who have no symptoms or mild signs that respond to supportive therapy like hydration, rest, and digestive support. Outpatient treatment for mild cases might include antiemetics (e.g., maropitant) to stop the vomiting, hydration, and careful nutritional support. Cats with symptoms from parvo may need hospitalization and even intensive care, including intravenous (IV) fluids, electrolytes, nutrition, antibiotics (if sepsis suspected), antiemetics, etc.[2]

While it is always best to consult with a veterinarian prior to administering any medication, even an OTC version, it is especially true for parvovirus given the potential for complicated symptoms and life-threatening illness. Always read the medication administration directions carefully and be on the lookout for potential side effects (like vomiting) when any medication is administered.

When-How Is Cat Stool Tested For Parvovirus?

Simply put, include a PCR test for Feline parvovirus whenever a cat has frequent or ongoing abnormal stools (soft stool or diarrhea) or other digestive problems. Need details? Read on.

Most of the time, parvo infections are not discovered unless veterinarians are searching for the cause of diarrhea or other digestive problems in cats or kittens. MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test with PCR Upgrade includes a Feline parvovirus by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assay along with PCR tests for other disease-causing protozoa, bacteria, and viruses found in cat intestines. These tests are designed to find the DNA (or RNA) of hard to find microbe pathogens. Screen for parvo in cats with signs of digestive upset, most commonly vomiting, with or without loose stool or diarrhea (which may have bile), loss of appetite, abdomen pain, decreased energy level, and fever.[2,7] Once found, vets may encourage pet owners to test other pets in the same household to determine if they are also shedding parvo .

Veterinarians recommend stool (fecal) testing kittens 2 to 4 times during their first year of life, and 1 to 2 times each year in adult cats (every 6 to 12 months). Veterinarians often call this stool health test a “Fecal O&P”, with the O&P meaning “ova (eggs) and parasites”. It includes special preparations of the stool sample and analysis using a microscope to look for roundworms, hookworms, tapeworms, whipworms, and some types of coccidia. Viruses and bacteria are not visible on an O&P stool test (included in MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test). Most of the time, a microbe by PCR test is used to detect the presence of parvovirus in cat stool (MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test with PCR Upgrade). Alternatively, veterinarians may have an ELISA viral antigen (protein) test at their practice to diagnosis a cat whose symptoms are suspicious of parvo . The ELISA test is especially valuable when test results are needed very quickly.

The MySimplePetLab Routine Cat Stool Test with PCR Upgrade screens for all five cat and dog parvo strain types (FPV, CPV-2, CPV-2a, 2b, 2c). PCR can be used to distinguish between the parvovirus strain types, but this is rarely necessary. The approach to treatment and prevention is assumed to be the same regardless of strain.[7,8] For this reason a MySimplePetLab parvo positive result does not distinguish between parvo strain types.

Additional Questions? Chat us at MySimplePetLab.com, email [email protected], or call us at 833-PET-TEST (833-738-8378).

Sources

- AVMA.org; Feline Panleukopenia

- Merck Veterinary Manual, Overview of Feline Panleukopenia

- Centers for Disease Control, Feline Host Range of Canine parvovirus

- Centers for Disease Control, Parvovirus B19 and Fifth Disease

- American Association of Feline Practitioners, Vaccines

- Greene Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat: Feline Parvovirus Infections, 3rd ed. St. Louis, Elsevier Saunders 2006, pp. 78-88

- Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, Canine Parvovirus

- The Veterinary Journal, Faecal Shedding of Canine Parvovirus After Modified-Live Vaccination in Health Adult Dogs, Vol 219, Jan 2017, pg 15-21

Page image source: Wikipedia